“The most important failure was one of imagination.”

—Final Report of the National Commission on Terrorist Attacks Upon the United States

We here at Third Factor will tell you that we love creativity. But what do we mean by that word? Is it something that belongs only to the realm of hobbies and self-expression, or can we apply it professionally, even if we’re not, say, novelists? Is there some way we can we use this thing we call creativity to serve an otherwise highly orthodox community?

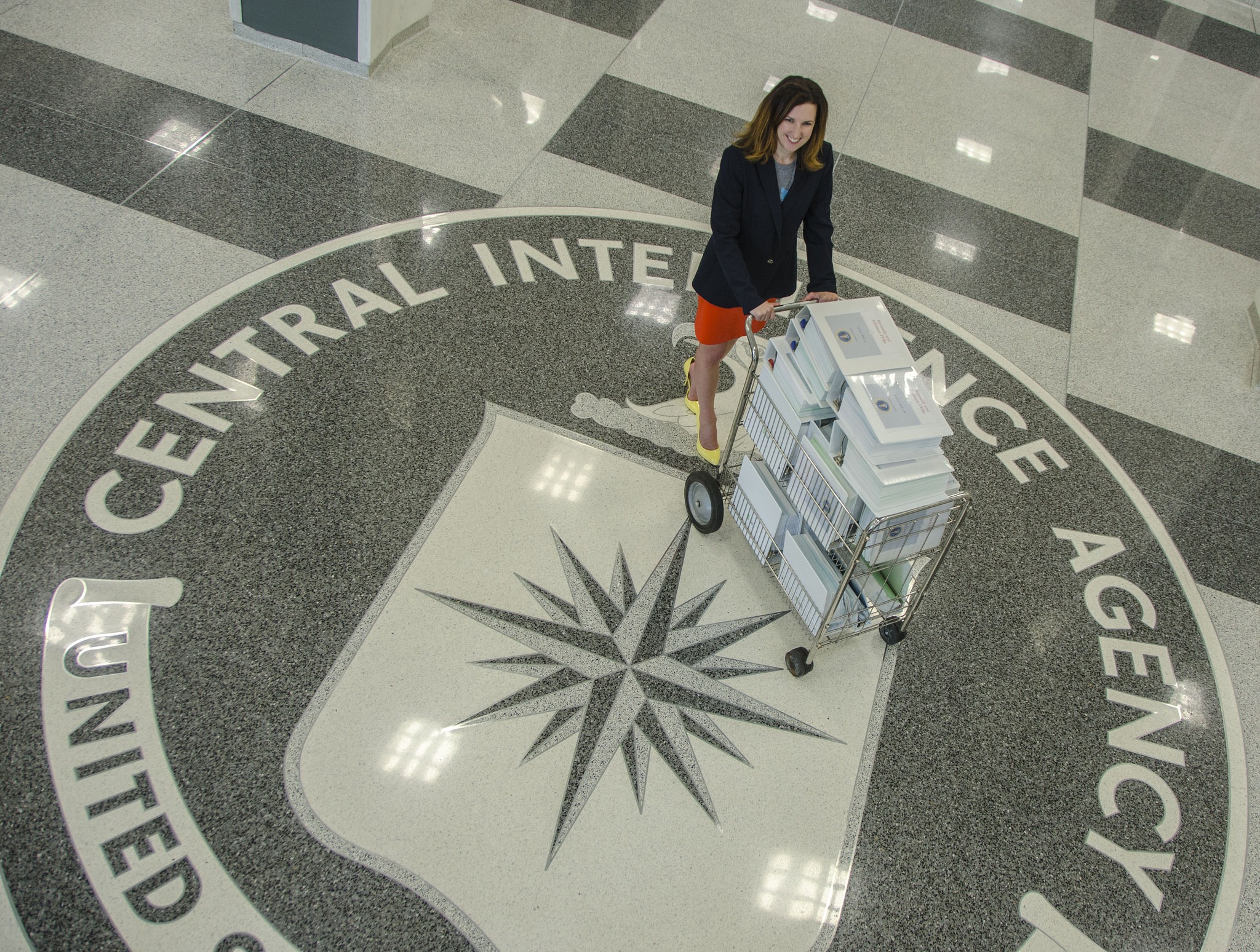

These questions are particularly salient for those “naturally creative” types who are prone to feeling like square pegs in round holes. They were certainly relevant to me when I worked as an intelligence analyst at the Central Intelligence Agency. (And for the record, I generally enjoyed that job and consider it a privilege and honor to have had that experience; I chose to leave for reasons that, while rather Dabrowskian, are outside the scope of this article. Perhaps I’ll share them here another time, but for now, I digress.)

One day, I participated in a team-building workshop for my small home analytic group. In one exercise, we were asked to identify our team’s top values; in keeping with the ethos of the Millennial generation, one of my younger colleagues suggested “creativity.” A few others nodded, but a more experienced analyst disagreed. Creativity, she asserted, really was not one of our guiding values.

I agreed. You see, I had recently tried to create a graphic that incorporated color, layout, and images to present my layered analysis in a way that policymakers would understand intuitively and quickly. When I went to work with the graphic designer to develop it, he noted that it was rare for an analyst to show up with something visual in mind; usually it was his role to suggest something. But he agreed that my idea was a good one, and he went to work creating what I described.

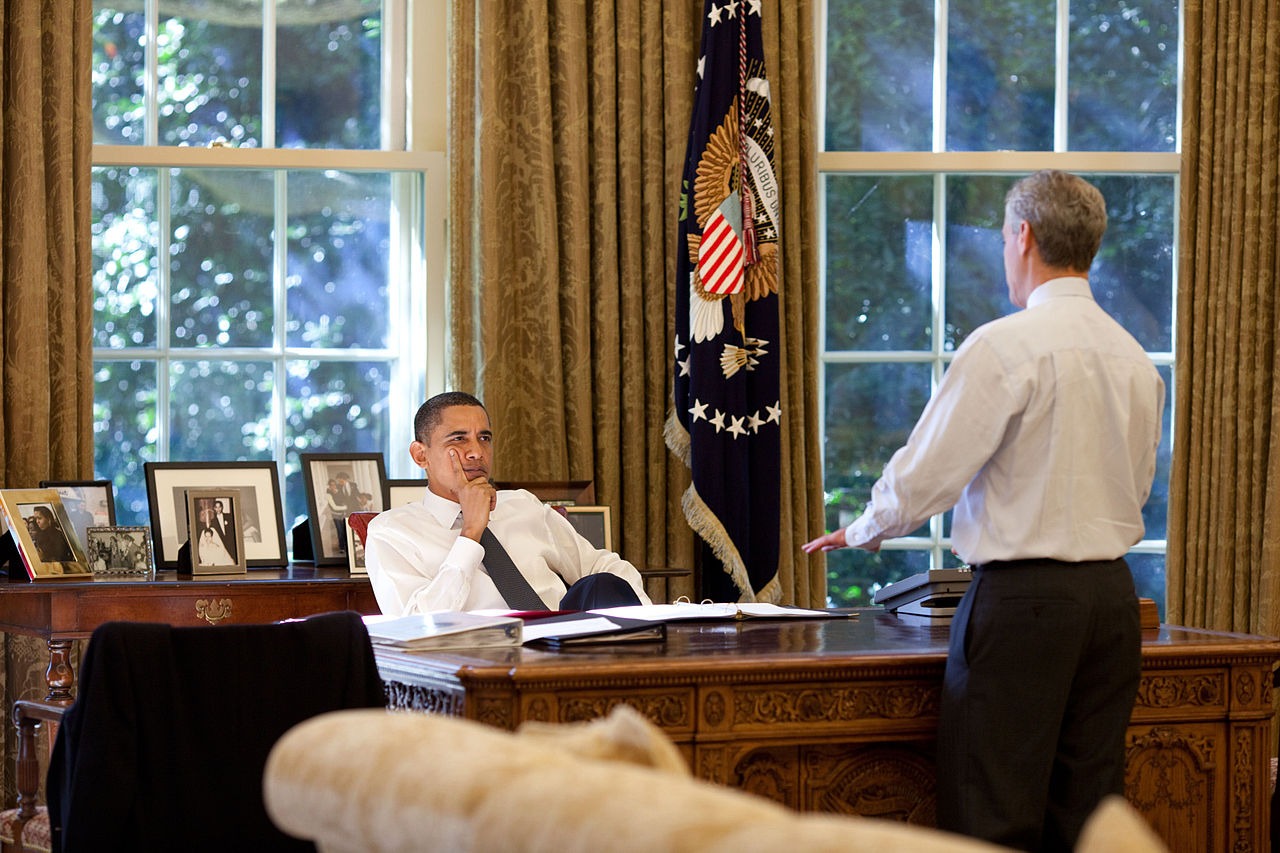

As it moved toward publication, however, someone along the Directorate of Analysis (DA) editorial chain asked if I hadn’t considered, you know, laying the information out with a standard DA template. I initially struggled to understand why it wasn’t obvious to the managers (in the same way it was to the graphic designer) that my custom layout would be more effective for this particular intelligence question. Happily, because I managed to articulate precisely how my format added value, my direct manager went to bat for me, and the graphic finally made its way to President Obama’s desk.

Nevertheless, the resistance to its publication suggested to me that, as my colleague had suggested, creativity isn’t one of the preeminent values in the DA. And there’s a reason for that: for the most part, an analyst’s job is about stringing together data in the way that the entire analytic team agrees makes the most sense. It’s not about any given individual coming up with an imaginative plot twist.

Except, of course, when that plot twist is about to happen in real life. Everyone in the DA agrees that they want to anticipate those. The example of terrorists crashing planes into buildings has become the archetype here: that no analyst had imagined (or, perhaps, was supported in imagining) that this might happen led the 9/11 Commission to cite “lack of imagination” as a key failure ahead of the September 11 terrorist attacks.

For the most part, an analyst’s job is about stringing together data in the way that the entire analytic team agrees makes the most sense. It’s not about any given individual coming up with an imaginative plot twist.

Except, of course, when a plot twist is about to happen in real life.

Unfortunately, “imagination” is a word that too often evokes cute children making fanciful drawings with crayons. And yet, the professional intelligence analyst absolutely must have that capacity which Merriam-Webster defines as

1 : the act or power of forming a mental image of something not present to the senses or never before wholly perceived in reality

2a : creative ability

That’s why, as part of the Agency’s response to the 9/11 Commission Report, the CIA’s Sherman Kent School for Intelligence Analysis developed a course called “Creativity in Intelligence.”

And when the struggle to get my graphic published revealed that I didn’t know how to advocate for my creative ideas in the face of the bureaucracy (“Why doesn’t anyone in management see what I see?!”), my manager suggested I sign up for the course to see if it might help. It turned out to be one of the highlights of my time in the DA. It also left me with insights that might be helpful to other imaginative professionals who are seeking to communicate with more orthodox colleagues—even in fields as weighty as national security.

Introducing a CIA Creativity Instructor

It was with that in mind that I sat down at the CIA Library to chat with Nyssa S., one of the instructors of Creativity in Intelligence, about how this course came to be, what it aims to do, and the impact it’s already had on the Agency.

Unsurprisingly, Nyssa is the sort of person who would be a kindred spirit to most Third Factor readers. When she took a career aptitude test in college, her results came back as “inconclusive.” Her tester suggested that perhaps she should be a garbage collector; Nyssa didn’t care for that idea, and continued her search. She eventually ended up in human resources, working for other organizations’ HR departments for several years before joining CIA.

Nyssa has a passion for developing others’ talent: she is a certified professional coach and works on talent development for the Agency. She’s even helped a few people on paths that led them to quit the CIA. “If you’ve tried several avenues and none of them got you where you wanted to go, it’s okay to do something totally different,” she said. “When people are happy, they are more productive.”

If you’ve tried several avenues and none of them got you where you wanted to go, it’s okay to do something totally different.

Nyssa S.

She originally encountered the “Creativity in Intelligence” course as a student—and found that it spurred a lot of ideas. She shared her ideas with the course’s instructor, and when he needed a new co-teacher, he invited her to come on board.

Divergence and Convergence

“My personal goal for the course is to help people handle the fact that they don’t know what they don’t know. That’s where the creative thinking comes in,” Nyssa explained. In pursuit of this goal, curriculum builders at the CIA’s Sherman Kent School modeled their course off of a degree offered at Buffalo State University in Creativity and Innovation.

And this, said Nyssa, “was off the reservation for the Agency.”

The culture clash has everything to do with the difference between convergent thinking and divergent thinking. This distinction is central to the course. Consider this definition of convergent thinking, which I found at psychologenie.com:

In simple words, convergent thinking is the ability to find the correct solution, without having a creative approach. A person is a convergent thinker when his sole aim is to find the best correct answer to a question. He will think in a way that is direct, precise and time-effective. He will use his knowledge on that topic, or refer to other solved answers and improvise it to get the best suitable solution, or create one of his own depending on the stated facts and information on the given problem. Convergent thinking comes to people who know to set their consciousness, focus, and targets on the problem they are solving.

This surely describes the archetypal intelligence analyst that my colleague had in mind during our value-naming exercise. Knowledge, efficiency, and precision in service of the best answer! What’s not to love?

Well, those terrorists in planes, for one. To propose on September 10, 2001 that suicide hijackers might use planes full of fuel to successfully bring the twin towers of the World Trade Center tumbling down would have required some powerful divergent thinking. Psychologenie.com goes on to define divergent thinking as follows:

The ability to think out of the box is divergent thinking. A divergent thinker thinks in a way that would include all the possibilities to get to a solution, giving creative ideas to make it work. This kind of thinking comes in a free-flowing manner, with no limitations to time and imaginations. The bondage of time doesn’t appear here, giving the person complete freedom to think about innovative and extraordinary ideas producing new results every time. You may or may not get the best solution, but various other ideas are sure to be conceived.

When I took the class, Nyssa and her co-instructor, Jacob, shared studies that found that DC knowledge professionals engage in divergent thinking a mere two percent of the time. And it’s true that the creative, free-floating image depicted in the passage above doesn’t tend to bring to mind “elite government professional.”

Studies show that DC knowledge professionals engage in divergent thinking a mere two percent of the time, but would do better if the ratio were closer to 20% divergence and 80% convergence.

Nevertheless, those same studies suggested that these elite professionals would do better if the ratio of their thinking were closer to 20% divergence and 80% convergence. In fact, they could do well with an even higher rate of divergence, as Nyssa’s co-instructor suggested to me privately later on. What the unusually divergent thinker ought to remember is that convergent thinking does tend to take more time—and that it, too, is essential to the process. But most divergent knowledge workers don’t need to be told that; the need to get the “right” answers is drilled into all of us starting early in our education.

What We Learn in CIA Creativity Class

With that background, it’s already a step outside the box to show up at creativity class. Before the five-day course begins, students are asked to choose a tough intelligence question in mind that they’d like to try to solve in a “creative” way, even if they’re not yet sure what that entails.

When they arrive at the classroom, they find crayons and pages from adult coloring books on every table. The instructors invite students to color freely during the class, though in my class, few did. (I was one of those few, in part because I knew that doodling helped keep my mind from wandering during lectures back in high school.)

To kick things off, the instructors explain that the class will explore creativity as a four step process, first identified by Alex Osbourne and Sid Parnes and detailed at FourSightonline.com:

1. Clarify → 2. Ideate → 3. Develop → 4. Implement

Clarification involves exploring the problem and making sure you are asking the right question—a particularly important part of intelligence analysis. Ideation means looking for as many solutions and ideas as you can; brainstorming is example of ideation and is a place where natural divergent thinkers often shine. Development involves refining an idea that you came up with in the ideation stage, bringing in the convergent thinking to make sure, for example, that your idea is appropriate and practical. And implementation is where you make it happen.

Over the week-long course, students explore what each of these steps entails and practice skills that facilitate that part of the creative process. By doing so, they gain insight into their strengths and weaknesses. “Some people are strong in more than one of these,” Nyssa explained, adding that a person with proficiency in all four modes is called an “integrator.”

One unit in the course focuses on meditation. CIA in general is pretty friendly toward meditation: I used to attend weekly drop-in meditation sessions in the library, and I also took a mindfulness course offered by the Europe and Eurasia Mission Center. But most CIA officers probably make use of those resources with the goal of managing stress and clearing their minds. It will not necessarily have occurred to them that meditation can help with creative thinking.

In another unit, students visit one of Washington, DC’s art museums. Keeping the intelligence problems they’re trying to solve in mind, they each select a piece of artwork that appeals to them and pause to look at it closely. This is meant to kick a different part of their brains into gear. If all goes well, students will come up with some useful insight as their musings about the art blend with those questions in the backs of their minds. A student who had success with the exercise asked the instructors, “Did you guys do this on purpose?” But as Nyssa noted, the students are doing the work of ideating themselves. The instructors merely showed them a way to think differently about their questions.

How best can we channel the power of art in our lives? It’s an issue Nyssa had grappled with earlier in her life. Her grandmother was an artist, and her teachers encouraged her to go to art school, but her grandma’s financial situation led her to reject that path. “Creativity didn’t pay the bills, so it was out,” she told me.

When she began to understand the role of ideation in the creative process, however, it opened a door to applying her creative skills in her professional life. Her ah-ha! moment was when she realized she could be professionally effective and creative. “I can create engagement and excitement around—let’s face it—very dull material,” she said. (Contrary to what the public may imagine, the classified questions that intelligence analysts dive into would bore most people. Even the policymakers you’re supporting often don’t know why they should care about your little top secret niche unless you can explain it engagingly.)

When Nyssa began to understand the role of ideation in the creative process, it opened a door to applying her creative skills in her professional life. Her “ah-ha!” moment was when she realized she could be both professionally effective and creative.

Ideally, at some point in the course, students will have that same kind of ah-ha! moment—one that will not only help them with their intelligence problem, but also with their quality of life.

No Longer Just Preaching to the Choir

When I took it in 2017, Creativity in Intelligence was an elective in the Kent School’s analytic training program. Since then, it’s been designated as a for-credit course in an advanced analytic training program, which has led to a change in the class composition. In the past, classes had more women than men, and most of the students—like me with my crayons—were already on board with the value of creativity, suggesting that the course was largely preaching to the divergent choir. In the first running after it was made a for-credit course, however, the class had six men and two women.

When the class reaches the unit on meditation, the instructors ask the students whether any of them have meditated before. Before the course was offered for credit, about fifty percent of the students generally raised their hands. In the first for-credit iteration, not a single student had tried meditation. After they tried it, however, one of the men raised his hand. “Can I do this every day?” he asked.

We sit at our desks for eight hours a day and are supposed to be cranking out original thoughts that whole time. But as we all know, this isn’t actually possible in reality.

Nyssa S.

The student’s question points to something truly significant about life in our nation’s highly convergent capital city. Though the new cohort of students are not the sort of people we tend think of as “naturally creative,” they nevertheless respond positively to the content. They understand the need for balance in life. Presenting themes like balance, divergence, and ideation in a formal, Agency-sanctioned course—a course tied to the analyst’s holy grail of critical thinking—appears to give them license to embrace and voice these values.

This in turn helps them address the particular challenges of being a twenty-first century knowledge worker. “Human beings have always done a lot of rote work,” Nyssa explained. “And while that wasn’t exactly fun, it did open space for a certain level of mindfulness. Now we sit at our desks for eight hours a day and are supposed to be cranking out original thoughts that whole time. But as we all know, this isn’t actually possible in reality.” If knowledge workers don’t understand how they come up with insights, it’s easy for them to get down on themselves—or their subordinates—for “slacking off” during the day. Old school managers often still balk at the idea of letting their employees take thirty minutes out of the day to meditate. But this, as Nyssa noted, means they just engage in a less effective but more easily disguised form of resting their brains known as “surfing the Internet.”

We should not be surprised to hear that the ah-hah! moment was bigger for the for-credit group than for the creativity choir. These students, Nyssa said, were more likely to go back to their home offices and actually implement change because they were excited about something new. They weren’t simply validating the way they’d always been trying to be.

Succeeding as a Divergent Thinker in a Convergent Organization

As a member of that choir, this rang true to me. I loved the course, but my main takeaway was indeed that of feeling affirmed by people who saw divergence as something to be emulated. The course teaches how to think more divergently, which leads to a rather different syllabus than you’d see in a workshop on how to succeed in the Directorate of Analysis if you’re naturally divergent.

But I’m glad that this new cohort is taking the class. See, the part of the process that received the least emphasis in the class was implementation. As a natural ideator, that happens to be my weak point in the creative process. As Nyssa noted, someone strong in implementation might complain that an ideator “is always off chasing squirrels.” (As an ideating analyst, I can confirm this.) But if those implementing, converging managers and coworkers take this class, they’ll be prepared to understand and collaborate effectively with ideating, divergent analysts. In other words, we don’t need to form a little support group for creative people; we need more convergently-inclined people to understand what we have to offer, how we can be of value to them and to the group in pursuit of our shared mission, and how we in turn benefit from their complementary strengths. An effective analytic team will have members with strength in each of the four stages of the creative process, and each member of the team will understand that process in its entirety. This will enable them to draw on each other’s strengths and make up for each other’s weaknesses—or, better yet, help them overcome them. Every analyst who signs up for Creativity in Intelligence brings the Central Intelligence Agency a step further along the path set out by the 9/11 Commission, thereby serving the American people.

When I reflect on the new cohort of students, I can’t help but think about the process of publishing my creative graphic. As it turns out, it’s now used as a template for other similar intelligence products. Through the process of fighting for it, I learned how to advocate for new ideas—how to successfully implement as a divergent thinker supporting people without the luxury of time for every shiny idea.

Ironically, the very fact that my graphic is now used as a template will help other analysts to develop and implement—that is, to converge—as efficiently as possible. I’ve actualized the idea that they helped me to make the best it could be; now they can repurpose it. Effectively applying creativity will always be this type of balancing act. That’s why, if you’re a divergently-inclined professional, your ultimate task is not to find the other “creative” types and hunker down with them. It’s to figure out how to communicate with and contribute to your team as you all walk that balance beam together.

Nyssa and her fellow instructor Jacob will present at this year’s South by Southwest conference in Austin, Texas on March 8, 2019! You can see a blurb about their presentation here.