As much as we celebrate overexcitability (OE) here at Third Factor, there is no getting around the fact that it is a disintegrating force. OE can be a terrible burden if you don’t learn how to manage it.

Fortunately, there are a handful of people out there who specialize in helping intense people do just that. P. Susan Jackson, founder of the Daimon Institute for the Highly Gifted in British Columbia, is one of them. Jackson works exclusively with exceptionally and profoundly gifted children, adolescents, and adults, whom she described as teeming with what psychologist and psychiatrist Kazimierz Dabrowski called developmental potential. But as Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration (TPD) makes clear, successfully realizing this potential is a tremendous challenge, in part because it involves mastering the disintegrating power of overexcitability. Jackson’s mission is to help her clients through this challenge, facilitating their efforts to learn to weather potentially positive disintegrations and avoid the truly negative ones. To this end, she has developed her own model, Integral Practice for the Gifted™ (IPG), inspired in part by TPD and by Ken Wilber’s integral theory, but informed above all by Jackson’s years of work with this special clientèle.

We at Third Factor sat down to chat with Jackson about how gifted, complex people can channel their intense thoughts and feelings, overcome the anxiety they often cause, and reintegrate themselves at a higher, healthier level.

What It Means to be Highly Gifted

So who are the exceptionally and profoundly gifted (EG/PG)? The groups are typically defined as those with IQs three (for EG) and four (for PG) standard deviations above the mean—a definition that falls flat in conveying who these folks actually are. Having done more than 80,000 hours of work with the EG/PG population, Jackson readily listed four key qualities that describe them: exceptional ability, very complex emotionality, particularly acute perception, and a tremendous capacity for nuance. She added that the cognitive aspect is broader than simply intellectual ability as measured by IQ tests, which on their own will not identify everyone who could benefit from her tailored services. One profoundly gifted person’s extremely nuanced perception of, for instance, social phenomena can be just as far from the norm as another’s ability to, say, play chess, wield vocabulary, or pour out creation; and indeed, they are each unique in their passions and strengths. Their capacity for absorbing and processing complexities also contributes to what for virtually everyone in this group is a truly idiosyncratic lived experience.

Jackson listed four key qualities that describe the profoundly gifted: exceptional ability, very complex emotionality, particularly acute perception, and a tremendous capacity for nuance.

Before we continue, a small editorial note from us here at Third Factor: though the exceptionally and profoundly gifted may be a very small segment of the general population, we think that you TF readers will find their experiences relatable whether you’re technically part of this group or not. It’s also worth noting that not everyone who is exceptionally or profoundly gifted (or even “just regular” gifted) realizes that they’re part of this population. Some are never identified as such; others are labeled after they grow up, when they go to a psychologist to try to discover what’s “wrong” with them and why they don’t fit in. This revelation might come as less of a shock if more people knew that being highly gifted is frequently less about reaching Einstein-like heights of intellectual achievement and more about having a mind—and body!—that takes in more, more, more, and processes it more intensely in an effort to keep up with it all. Fortunately, while you might need official identification to get special school services or join a high IQ society, you don’t need anything like that to know whether Jackson’s insights resonate with you. If you find yourself relating to what she says, we suggest you try her guidance on for size whether you were in the gifted program or not.

Positive Disintegration for the Gifted and Depressed

Jackson stumbled across TPD years ago while studying extreme major depression in profoundly gifted youth. She took a phenomenological approach to the subject (that is, a focus on subjective experience), so her research centered on interviewing bright kids who were tremendously sad, frustrated, and hurting. “I asked them, ‘What has been your experience with less than positive mental states?’ I don’t like the D-word,” Jackson said. “In every case, the kids started laughing when I said, ‘less than positive emotional states.’ They knew I was giving them permission to explain their emotional landscape.”

The interviews revealed the youngsters’ incredible richness and depth of experience. And while it made sense that such depth would contribute to their inner turmoil, she didn’t have a good lens to make sense of it—until she stumbled across TPD. “I had never heard the word ‘Dabrowski,’” she said, “but someone said I should send these protocols off to [Dabrowski’s former colleague] Michael Piechowski. So I sent lengthy transcripts on these twelve kids.” As it happened, the young man who prepared the transcripts was also profoundly gifted, giving rise to a confluence between Jackson’s ability to elicit her clients’ experiences, the experience of the transcriptionist, and content of the interviews themselves—and leading Jackson “down the the rabbit hole” into the world of the profoundly gifted.

It also got her an invitation to the Dabrowski Congress, a biannual gathering of those seeking to further their understanding of TPD. “I’d never studied Dabrowski, so I came in through this phenomenological lens, and these children so matched what we expect high developmental potential to be.” As Dabrowski defined it, developmental potential is the constitutional endowment that determines the level of development a person can reach—if environmental conditions are optimal. (Dabrowski, 1996, p. 10) Overexcitability contributes to developmental potential, but realizing that potential requires an environment in which a person can learn to manage the disintegration to which this same OE will eventually give rise. According to Jackson, her subjects’ experience of disintegration matched this precisely.

Integral Practice and Autopsychotherapy

Managing overexcitability and overcoming disintegration essentially require you to learn to be your own therapist, a dynamic process that Dabrowski called autopsychotherapy. It’s essentially this process that Jackson seeks to teach her clients.

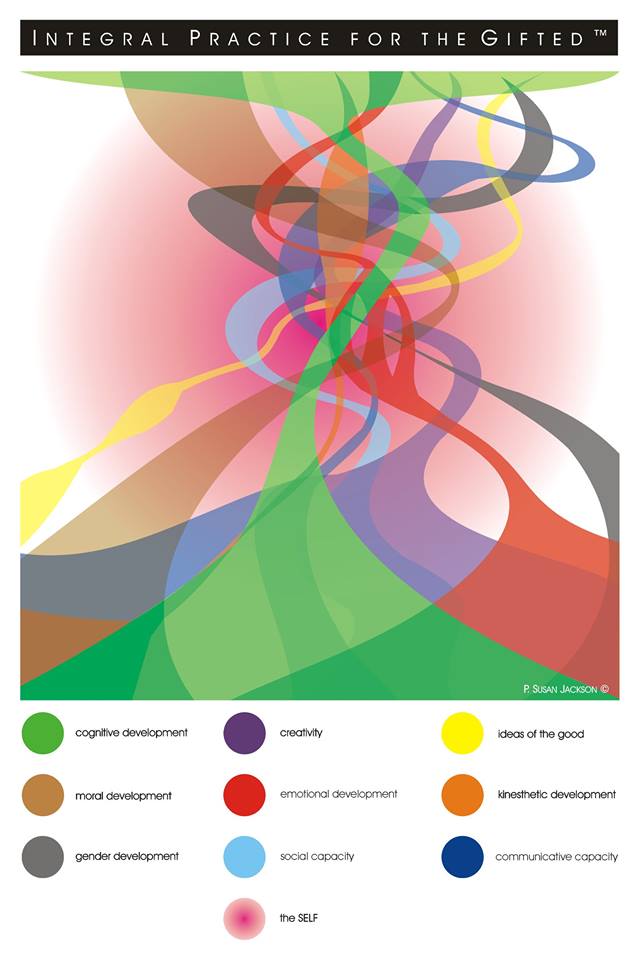

“What I feel I’m able to craft is a kind of ‘autopsychotherapy’ environment within my own integrative model that looks at a whole lot more,” she said. Jackson was clear that she’s in no way an orthodox Dabrowskian; rather, she’s taken Dabrowski’s findings and woven them with other theories and her own experience to develop IPG™, tailored to the unique needs of her exceptional clients. IPG™ is comprehensive and holistic, addressing the gifted child’s development not just in the intellectual domain, but also the emotional, social, physical, moral, spiritual and talent-based domains. “It looks at the kinesthetic. It acknowledges communicative, aesthetic, and social dimensions. And gender—that one’s rich and highly misunderstood!” Jackson added. According to Integral Psychology, all of these different elements are essential to growth and development. She showed me a small poster of many colorful threads wound together, depicting how the various domains all connect and overlap. “We have the poster up in the treatment room, and the kids refer to it constantly,” Jackson said.

The colorful threads, moreover, overlay a pink core. This represents the Self, which is the ultimate compass in the practice of IPG™. “My model has Self-as-process,” Jackson said, comparing this Self to Dabrowski’s conception of personality. In the language of TPD, not everyone has personality; rather, we each have an ideal at which we are aiming, and only once we have reintegrated ourselves in line with that ideal can we say that we have “achieved personality.” Jackson’s concept of the Self is similar. The process, she said, involves asking, “At various stages in my evolution, what am I called to be?” The Self must coordinate all the various domains that contribute to a person’s development, said Jackson. “So my job as a clinician is to support the Self.”

The five types of overexcitability that Dabrowski identified are represented in the colored threads on the IPG poster, which helps us visualize how Jackson helps her clients make sense of them. As an example, she spoke of a boy whose intellectual OE was obviously “through the roof” and whose emotional OE was “subverted.” “The emotional OE was pulling everything else down,” she said, gesturing toward the IPG poster. It’s easy to see from this illustration how tugging on one thread will drag the whole Self down with it, warping the overall development; or in Dabrowskian terms, undermining one’s access to higher levels of development.

Disintegration and the Will

Scholars like Leta Hollingworth and Miraca Gross who have studied the highly gifted came to the same conclusion that Jackson reached after working with this population: will and intellect are one and the same. “If there’s one thing about a PG person that’s an earmark, it’s that incredible sense of self that you have from birth,” Jackson said. “You don’t know that that’s very unusual, to have such a strong compass” that drives you to contribute, to seek to understand—and do—what’s right in the world. “That will of yours is a beautiful thing,” she said. “We need to use that in service of yourself, to help you evolve in the world, in service of other people.”

Scholars who have studied the highly gifted came to the same conclusion: will and intellect are one and the same.

But having a very strong sense of Self, a very strong perception of purpose, gives rise to its own challenges. She spoke of a young child who had been diagnosed with oppositional defiant disorder (defined in the DSM-5 as “a pattern of angry/irritable mood, argumentative/defiant behavior, or vindictiveness” in children and adolescents) because of his tremendous will, which was in turn fueled by his remarkable intellect. “This kid’s fighting to hold on to his personality ideal,” she said. “He’s a little warrior without a game plan; a warrior without a team.”

If will and intellect are so strongly linked, moreover, then it’s no surprise that thwarting a strong intellect often gives rise to anxiety. In 1949, pioneering psychologist Howard Liddell wrote that he had “come to believe that anxiety accompanies intellectual activity as its shadow and that the more we know of the nature of anxiety, the more we will know of intellect” (Liddell, 1949, p. 185). Jackson said that her work quickly led her to the same conclusion. “You can tease apart OE and anxiety for discussion purposes,” she said, “but OE are disintegrative mechanisms in and of themselves because they cause you to be aware, to wonder “what if,” to make patterns, to be more literally enervated, to have the energy, to think longer than the average guy. And I accept that. It’s a wonderful thing.”

At the same time, this can frequently be a painful, frightening, confusing, and overwhelming experience. Jackson’s clients face both mental and physical constriction as they try to expend that energy and realize that “what if.” When this happens, she guides the children to come up with their own path through it. “I was teaching a kid today how to be completely disintegrated, with a classical anxiety response—to stay grounded and accept it and ride it, and to develop any number of strategies to work with it in a very real way,” she explained. Understanding anxiety through the lens of overexcitability, she said, helps children learn to put themselves in a dynamic state—a state of potentially positive disintegration, in which they can identify and address whatever it is that is dragging their Self down. “The kid has to tell me how s/he can use [that intense reaction] in a positive way,” she said. “This helps them avoid the sense that they’re falling apart.”

Understanding anxiety through the lens of overexcitability helps children put themselves in a dynamic state in which they can identify and address whatever it is that is dragging their Self down.

Dabrowski’s dynamisms, she added, have turned out to be useful tools for teaching children, though usually they only want a brief explanation of what the various dynamisms refer to. After that, they tend to be eager to do the real, hands-on work of engaging with their own messy dynamisms.

She also insists that the kids get out of their heads. “I want response from the viscera,” she said. She instructed one child struggling with a disintegrative reaction to clutch a pillow and rock back and forth. “He said he had the most amazing experience! He had been relying only on the cognitive, never the emotional, sensual, gender. All that was getting squeezed out.” By clutching the pillow to his gut and noting his feelings, he managed to get away from an overly intellectual approach to his disintegration. “You cannot reason out of these things,” Jackson explained.

Jackson also stresses with her clients that it’s okay to disintegrate, especially when you’re in a period of rapid growth. This might involve what Dabrowski termed a “positive regression,” in which the child or adult returns to whatever feels safe and comfortable in order to take a neurological break. “It’s okay to be in a disintegrative state, but it’s not okay to stay there for a long, long time if it’s causing the physiological problems that we call anxiety,” Jackson said. “More than likely, you have a lot of adrenaline running through your system.”

What, then, should we do if we do get to that state?

If it’s caused by something noxious that’s happening in the environment, Jackson said, she aims to teach a child how to use her tremendous response to overcome the stressor. Though an overexcitable, gifted mind can contribute to suffering in these situations, it also offers the means to overcome the suffering, Jackson said, “because you’re capable of thinking a little more and understanding your bodily reactions.”

What about when she is working with gifted adults? “I have a binder full of language about emotion, and I might tell you to pick three words about emotion that resonate with you today,” she said. With kids, she does essentially the same thing through the power of play. “I pretended with this kid that I was a receiver of anger, so we know that anger isn’t bad.” And that way, she explained, “we embodied anger.” This, she reiterates, cannot be done through the intellect alone.

What Gifted, Intense People Should Look For in a Therapist

Finding a therapist who understands what’s normal for highly gifted or overexcitable people can be enough of a challenge to discourage them from ever getting it, even if they could really benefit from some guidance in kickstarting or checking on their own autopsychotherapy processes. To that end, we asked Jackson what these people should look for to increase the odds that they’ll find a therapist who can successfully address their unique needs.

First, your therapist should understand that though the experience of the highly or profoundly gifted person is uncommon, it is a normative development. One particularly relevant part of the gifted norm is the experience of asynchronicity, or the notion that an individual may be highly developed in one domain (frequently but not always the intellectual) while other domains languish in underdevelopment. But, Jackson specified, this isn’t “built into the cake; it’s the way the cake gets cooked. There’s a huge difference.” There’s a good chance that whatever’s motivating a highly gifted person to seek therapy has to do with being baked—or rather, raised—in an environment that just wasn’t prepared to deal with their asynchronicity.

All this points back to the need for a therapist who takes an integral approach, meaning that they understand how the interweaving of all those various domains affect our lives. If a gifted adult was never pushed to develop anything but the cognitive domain, they’re going to struggle, Jackson emphasized. “A very intellectualized person is just being a ‘smart guy.’ They’re not being full, integrated people,” she said.

Ultimately, whether you are profoundly, moderately, or technically not at all what we call “gifted,” if you are seeking therapy, you’ll want someone who helps you discover your personality ideal and what might be dragging you down, preventing you from moving toward it. Jackson emphasized that she strives “to create an environment where you will literally sink into your deepest self, and toggle and move and suddenly get insight into yourself.” This, ultimately, is how a good therapist helps you develop the capacity for that dynamic autopsychotherapy that will continue, long after you’ve concluded your course of therapy, to help you realize your unique Self.

Enjoy this piece? Find more like it at the Third Factor homepage. Or consider subscribing to our monthly update: