On the borderline of levels III and IV inner conflicts are strong. In these conflicts, doubt, depression, states of anxiety are converted into developmentally positive action.

—Dabrowski, 1996, p. 41

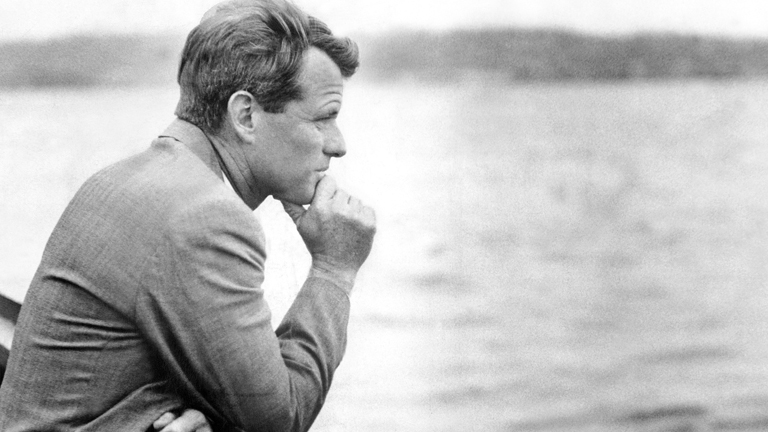

Then, with brutal suddenness, Robert Kennedy stood alone. JFK was dead. Their father, crippled by a stroke, could only utter the word ‘no.’ Robert Kennedy had no one left to serve and protect. He had to remake himself, to find a new role. He escaped into brooding for a long time, then slowly rejoined the world. Events pulled at him, forced him to weigh his capacity to lead—and his courage. Anguished, uncertain, he hesitated, pulled back—then lunged forward. His entry into the 1968 presidential race—criticized as belated and opportunistic at the time—required an act of tremendous personal will. Kennedy was able to transform himself from follower and behind-the-scenes operator to popular leader in part by conveying, in an urgent, raw way, his identification with the underdog.

—Thomas, p. 19-20

On November 22, 1963, Bobby’s brother was shot and killed, and everything changed.

As we saw in our last issue, Robert F. Kennedy was a decidedly overexcitable man who seems to have experienced small positive disintegrations after (relatively) small crises. This is certainly one way that people can experience positive disintegration and reintegration.

Then there are the calamities. JFK’s assassination was the cataclysm that finally wiped away what remained of RFK’s previous integration. It seems to have been held together largely by second factor forces (i.e., social and environmental influences, or “nurture”) in the form of his strong sense of duty to his family. Now that he was no longer his brother the president’s right hand man, he felt utterly without orientation.

And while Bobby’s friends found his grief understandable, they were nevertheless struck by its all-consuming nature. According to biographer Evan Thomas, author of Robert Kennedy: His Life (Ed. note: all citations are to Thomas’s work unless otherwise noted), he was completely overwhelmed. His grief not only dragged on, but seemed to deepen as the weeks passed.

The lens of Kazimierz Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration (TPD) is useful in our attempt to understand what that this intense man must have been going through. After all, as Thomas notes, Robert Kennedy “was a sensitive man who always seemed to feel more deeply than most” (283). Sensitivity and depth of feeling are forms of emotional overexcitability (or emotional OE for short) that contribute to what in TPD is called developmental potential. Unfortunately, Dabrowski also said that breaking down under the weight of these feelings is generally part of the process of realizing this potential.

RFK left plenty of evidence that this process was unfolding inside him. On a legal pad found in his papers from about that time, he had scrawled, “The innocent suffer—how can that be possible and God be just”, and “All things are to be examined & called into question—There are no limits set to thought” (285). These statements are straight out of Dabrowski’s level III, the level of spontaneous multilevel disintegration, in which the sufferer’s disintegration is thrust upon him, leading him to suddenly recognize higher and lower paths and to begin to imagine where they might lead.

Robert Kennedy’s imaginational overexcitability left him haunted by the fear that his pursuit of Castro and the Mafia had tipped the first domino in a chain that led directly to his brother’s murder.

People are sometimes inclined to think of “imagination” as the happy wellspring of children’s colorful crayon drawings and award-winning novels. But imaginational overexcitability can also curse those who have it, making it all too easy for them to envision possibilities that are quite dark indeed. In Robert Kennedy’s case, his imaginational OE left him haunted by the fear that his pursuit of Castro and the Mafia had tipped the first domino in a chain that led directly to his brother’s murder. It must have been easy for him to imagine just how it would have played out, even without the help of the conspiracy theorists who were so eager to fuel that fire.

JFK was not, moreover, the first sibling Bobby had lost. His eldest brother, Joe Jr., died while flying a dangerous mission in World War II; his elder sister Kathleen died in a plane crash a few years later. With such abundant evidence of life’s dangers, it’s easy to imagine why Bobby would have made courage a keystone of his personality ideal.

Courage: RFK’s Path to Reintegration

In TPD, courage is considered a function of personality. In this context, “function” is basically a fancy term for an expression of behavior that’s fueled by cognition or emotion. Functions, which range from sincerity to infantilism to religious belief to sexuality, give us a glimpse of who a person is and what Dabrowskian level they’re at. In Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions (1996), Dabrowski and his colleagues offer an in-depth exploration of many functions and describe what they looked like at each level.

The descriptions Dabrowski offers of courage at each level shed light on Robert Kennedy’s growth. During the unilevel disintegration that characterizes level II, says Dabrowski, “courage may be impulsive as a function of enhanced psychomotor overexcitability” (1996, p. 123). We saw level II courage clearly in Bobby’s early life; by the time his most profound disintegration begins, now in his late 30s, remnants of level II linger. We see him, for instance, diving into fifty-degree Fahrenheit water to rescue his late brother’s jacket after a gust of wind blows it into the sea (308). We also see him, wholly inexperienced as a mountaineer, preparing to climb a mountain named in his brother’s honor by running up and down the stairs “practicing yelling ‘help’” (307)—and then climbing the mountain anyway.

This stands in contrast with courage at level III. In this level, as multilevelness emerges, courage comes more under conscious control and separates from the impulsive bravery of lower levels. It is replaced with a more determined, more aware, more balanced expression. The former is bold and quick; the latter “grows quietly under the surface” to become strong and lasting, giving its bearer a quiet power and awareness (Dabrowski, 1996).

It would seem that, in Bobby’s case, it did need to grow quietly under the surface. Inner transformation is no easy task. Bobby therefore retreated into himself, and into stories that helped him make sense of his experience. As he read the works of the ancient Greek playwright Aeschylus, he saw himself in Agamemnon in the noble and doomed house of Atreus. He also discovered and devoured a book called The Greek Way, in which author Edith Hamilton essentially describes a profound Dabrowskian disintegration when she declares, “Tragedy’s one essential is a soul that can feel greatly.” Few souls, says his biographer, ever felt more than Robert Kennedy’s—a sure sign that Thomas is describing a man with emotional overexcitability.

But sometimes, growth happens after the most horrific tragedy. Thomas makes a good guess as to why it happened to the grieving Robert F. Kennedy: “No longer concerned with embarrassing his brother, he was allowed to develop his own quirky style, quite different from his brother’s rhetorical eloquence and cool detachment” (294). In other words, the grip of second factor social pressures on RFK lessened, and the third factor took control.

The Victory of the Third Factor

“The true nature of anything,” Aristotle says, “is what it becomes at its highest.” Not the embryo, but the full-grown man; not any man, but man at his greatest.

—Jotted in RFK’s daybook, from a reading by Edith Hamilton

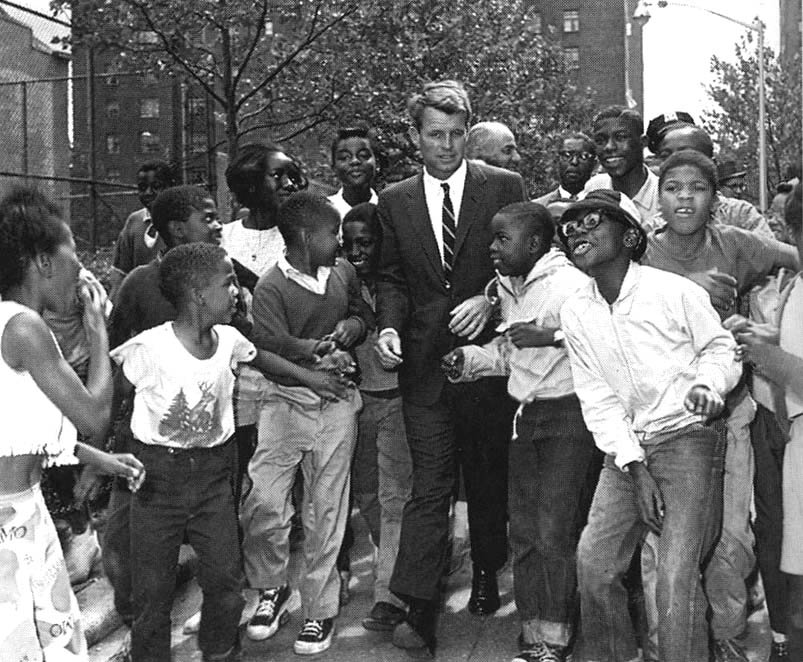

Even as he seemed lost in his stupor of grief, something was happening inside Bobby Kennedy. The things he had witnessed as attorney general—the poverty and racism he wouldn’t have known growing up in a white family with incredible wealth—cranked the dynamisms of empathy and responsibility up to full power. Moreover, his willingness to learn, suggesting the dynamism education-of-oneself, led him to become passionate about fighting against poverty and for racial justice.

It began with simple acts of imagining himself in someone else’s shoes. After a briefing on the causes of juvenile delinquency while he was still attorney general, for instance, he had responded, “Oh, I see—if I had grown up in those circumstances, this could have happened to me” (306). Sometimes he did miss the mark, as when he tried in a conversation with black activists to compare the discrimination faced by his Irish grandparents to that faced by blacks, but he also listened and changed his views based on what he heard.

“You don’t know what I saw! I have done nothing in my life! Everything I have done was worthless!”

Senator Robert F. Kennedy, after visiting families living in poverty

When he laid eyes directly on abject poverty, it cut him to his core. In 1967, RFK went to visit poor black families in the Mississippi River delta. There he interacted directly with children whose bellies were distended by starvation. His daughter Kathleen remembers him walking in upon his return home, “ashen-faced” and agitated, and trying to convey what he saw to his children as they ate dinner: “The children are covered with sores and their tummies stick out because they have no food. Do you know how lucky you are? Do you know how lucky you are? Do something for your country.” The wife of an aide remembered an exchange with him the following day: “‘You don’t know what I saw! I have done nothing in my life! Everything I have done was worthless!’ He was so shaken, so self-deprecating about his life. Mississippi was the worst thing, he needed to dedicate his life to this” (339).

The Decision to Run

The phase of spontaneous multilevel disintegration is characterized, as its name indicates, by multilevelness and spontaneity. Its main trait consists in the hierarchization of values and in the operation of such dynamisms as astonishment with oneself, dissatisfaction with oneself, disquietude with oneself, maladjustment to oneself and to the environment. At this stage of his development, the individual is under constant pressure to “transcend” the rigidity of a unilevel structure and to activate creative dynamisms.

The directed phase of multilevel disintegration is characterized by its organizing, systematizing role, by the growth of consciousness and self-control, by systematic experiencing and separation of different levels in oneself (the dynamism “subject-object” in oneself, the third factor), by inner psychic transformation and the growth of empathy. This Phase enters into secondary integration, i.e., the mature personality.

—Dabrowski, 1973, p. 44

Bobby had seen a higher path. He knew that he was in a position to do something about the suffering he saw. But when it came time to decide whether to throw his hat in the ring for the Democratic Party’s 1968 presidential nomination, he wavered.

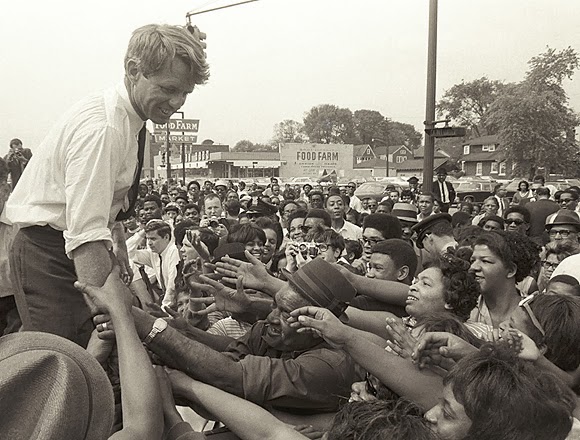

“As always, his better angels competed with his baser instincts,” Thomas writes. Journalist Pete Hammill goaded him by showing him photographs of his brother’s portrait hanging in the homes of the poor. It was his obligation, Hammill told him, to “stay true to whatever it was that put those pictures on those walls” (357). Other friends noted that RFK was radiating physical and emotional stress as he dithered, in keeping with the tremendous stress of level III’s spontaneous multilevel disintegration. In the language of TPD, he was full of disquietude and dissatisfaction with himself, trying to face the hierarchy of values that had made itself clear to him.

Then he decided to run, and his tension was resolved, with those who knew him describing him as clearly “relieved” (359). The tension was, of course, immediately replaced by the stress of campaigning, but though this was indeed tremendous, it was a stress that is compatible with the directed multilevel disintegration of level IV. Bobby seemed to feed off the crowds that turned out for him. He refused to ride in covered cars because that would prevent him from engaging directly with the people. More than once, the crowds made off with his shoes.

He was also honest with voters. Facing an audience of white, middle class medical students quite unlike the crowds pictured above, he was challenged on his plan to provide more health care for the poor. “Where are you going to get all the money for these federally subsidized programs you’re talking about?” a future doctor asked. “From you,” Bobby told the student, and continued despite boos and hisses, citing Camus for backup: “If you do not do this, who will do this?” As a few in the crowd started to clap, he continued: “You sit here as white medical students, while black people carry the burden of the fighting in Vietnam.” By the time he was done, Thomas reports, Kennedy won grudging but respectful applause (371).

It may be counterintuitive to some who are imagining stereotypical politicians, but it’s in line with TPD to note that the campaign brought out Bobby’s childlike qualities. As we noted in Part I, readers with a background in gifted education may understand this trait as asynchrony; Dabrowski described it as a function called infantilism, and noted that the positive type is common in artists, visionaries, and others with strong imaginational and emotional overexcitability (Dabrowski, 1996, p. 141). Thomas highlights a scene during the campaign in which a crowd pressing in on Kennedy, and a spectator cries out, “There’s a little boy there! Watch out!” The spectator was referring to a small child who had been swept into the crowd, but without missing a beat, Kennedy responded, “Yes, he’s a U.S. senator” (21). Far from being confident in his political power, here was a man who clearly identified with those who are very small, with a lot of growing yet to do.

And yet, this man who had once been described as a little boy in a grown-up suit fully understood the danger he faced. His own brother’s assassination in an open car had been seared into his mind. Thomas cites at least two times that Bobby jumped in terror at the sound of party snappers, including his own fortieth birthday celebration (310). Less than a month after he launched his presidential campaign, he was confronted with the reality of yet another assassination, this time of Martin Luther King, Jr. About that time, Bobby copied a passage from Camus into the daybook he carried with him: “Knowing that you are going to die is nothing.”

This man who had once been described as a little boy in a grown-up suit fully understood the danger he faced. Thomas cites at least two times that Bobby jumped in terror at the sound of party snappers, including his own fortieth birthday celebration. About that time, Bobby copied a passage from Camus into the daybook he carried with him: “Knowing that you are going to die is nothing.”

In TPD, we often speak of people “reaching” a certain level. If we zoom in, however, we usually see more of a mosaic of development. A person may, for example, have some functions at level II, many at level III, several at level IV, and one or two in which they consistently function at level V, giving him an “overall” level that is the average of all those separate colored tiles of character. It seems to me that, on average and despite his flaws, Robert F. Kennedy reached level IV in the last months of his life, and that a couple of the most prominent tiles of his personality mosaic—the ones for which we remember him—were those in which he embodied level V.

Dabrowski describes political behavior as a function in Multilevelness of Emotional and Instinctive Functions. The themes of RFK’s campaign for the presidency are those of a man with enough of a knack for self-education to learn how the world really was; who was moved to action by empathy for children who lacked what his children had; who was driven by a visceral responsibility for righting this wrong. All of these are dynamisms that Dabrowski cites for the function of politics at level IV in Multilevelness. And what of level V? Consider this passage in which Dabrowski describes politics at the highest level:

Professing and realizing full harmony between beliefs and actions. In politics one is governed by identification and empathy stemming from authentism and education-of-oneself. In a synthetic approach to politics one reaches towards transcendental morality. Principle: “My kingdom is not from this world” yet, in part, it is for this world. (1996, p. 153)

I leave it to you, dear reader, to decide whether Bobby’s campaign makes the cut. One thing at least seems clear enough: to be such a leader, one must have courage. And in Robert Kennedy’s courage, again, may have reached the ideal.

On the afternoon of June 4, 1968, at a beach in California where his father had been campaigning ahead of that day’s primary election, Bobby’s son David got caught in a riptide and pinned underwater. His father, who was taking a much-needed rest on the beach as voters went to the polls, dove in to rescue him.

Dabrowski wrote that at level IV, courage is “always connected with the feeling of responsibility for oneself and for others and with the development of autonomy and authentism”; at level V, it is “full awareness in carrying out the responsibility of the highest moral values, even to giving up one’s life for their sake” (1996, p. 124). Recalling that we are speaking of a man who would duck and cover at the sound of a party cracker and yet knowingly risked his life in a crusade to address the suffering of those less fortunate, it seems likely that when it comes to courage, Robert Kennedy reached level V.

Indeed, above a certain developmental level, knowledge of the fleetingness of life seems likely not hinder, but rather to fuel courage. As Bobby wrote in his daybook: “We may all be doomed, but each man must define himself anew each day by his own actions” (22).

Political Leadership and the Personality Ideal

Jack Kennedy was more the politician, saying things publicly that he privately scoffed at. Robert Kennedy was more himself. Jack gave the impression of decisive leadership, the man with all the answers. Robert seemed more hesitant, less sure he was right, more tentative, more questioning, and completly honest about it. Leadership he showed; but it had a different quality, an off-trail unorthodox quality, to some extent a quality of searching for answers to hard questions in company with his bewildered audience, trying to work things out with their help.

—John Bartlow Martin, quoted in Thomas, p. 390

Evan Thomas calls Robert F. Kennedy “one of a kind” (24). In politics especially, perhaps he is. He was “the Kennedy who most intensely experienced the range of human emotions” (28). Overexcitability, nonconformity, and asynchrony such as he showed would presumably be barriers to anyone who wasn’t born into a well-connected, wealthy dynasty—and even to those who were, if circumstance weren’t to step in and cruelly open a way forward. Perhaps there is a reason that neighbors heard Bobby playing the song “The Impossible Dream,” that classic ballad of quixiotic ideal from Man of La Mancha, over and over in his New York apartment (320).

In our cynical age, it’s reasonable to fear that anyone revealing glimmers of functions at level IV-V will never reach a position of leadership. But the response—then and now—to Bobby Kennedy’s campaign gives me hope that, in some other unrepeatable story, some such person may still turn out to be the right person for the moment, overexcitability and all.

Life will not be easy for this person. Disintegration, even the positive kind, is painful, and such a person is sure to have been through it. In his copy of Edith Hamilton’s The Greek Way, Bobby underlined a passage from Aeschylus that seems to describe the process: God, whose law it is that he who learns must suffer. And even in our sleep pain that cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despite, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God. (Thomas, p. 287 / Hamilton, p. 82)

God, whose law it is that he who learns must suffer. And even in our sleep pain that cannot forget, falls drop by drop upon the heart, and in our own despite, against our will, comes wisdom to us by the awful grace of God.

Aeschylus, quoted by Edith Hamilton and underlined by Robert Kennedy

As he went through his disintegration, Bobby Kennedy sought existential heroes. Perhaps the overexcitable and dynamic are inclined to yearn for such models as they follow their unrepeatable paths. Now, for many of us, Bobby has become one himself. He had faults and made mistakes, to be sure. The lens of positive disintegration, happily, can make it easier to find role models and grapple with their imperfections by offering a focus on growth. All of you imperfect people who seek to make a difference but know you don’t fit the mold may like this passage from Emerson, which Bobby saw fit to underline: “When you have chosen your part, abide by it, and do not try to reconcile yourself to the world.”

The emotionally overexcitable among you may also find comfort in a passage from Camus that Bobby copied into his daybook: “Perhaps we cannot prevent this world from being a world in which children are tortured. But we can reduce the number of tortured children. And if you believers don’t help us, who else in the world can help us do this?”

Eventually, Bobby put it in his own words. You can now find them carved beside his grave at Arlington National Cemetery; or recorded from the speech against apartheid he gave in South Africa in 1967: