There’s a certain character profile that turns up a fair amount in the Third Factor sphere. Let’s call him or her the agreeable questioner.

I’m inclined in that direction myself, and the collision of these two traits surely contributes to my interest in positive disintegration. Asking questions and sharing when you see something differently (i.e., disagreeing) clash with the desire to belong and uplift people. So if you’re temperamentally inclined both to agreeableness and to questioning, you’ll probably also want to level up your social graces.

That’s why I wanted to talk to Andrea Lynn Lewis, a Canadian stay-at-home mom of three boys (ages ten, eight, and five) who runs a popular Twitter account and a YouTube channel. Her balance of intellectual exploration and cheerful agreeableness is one admirable model for people seeking to develop those high level graces.

It always looks easier from the outside, doesn’t it? Because it turns out Andrea is no stranger to the experience of positive disintegration herself.

Agreeableness and Openness

To understand why, let’s start with how she sees herself. Curiosity is a big part of Andrea’s self-concept. “I wonder things a lot,” she told me. “Some people are happy to accept things; I need to know why!”

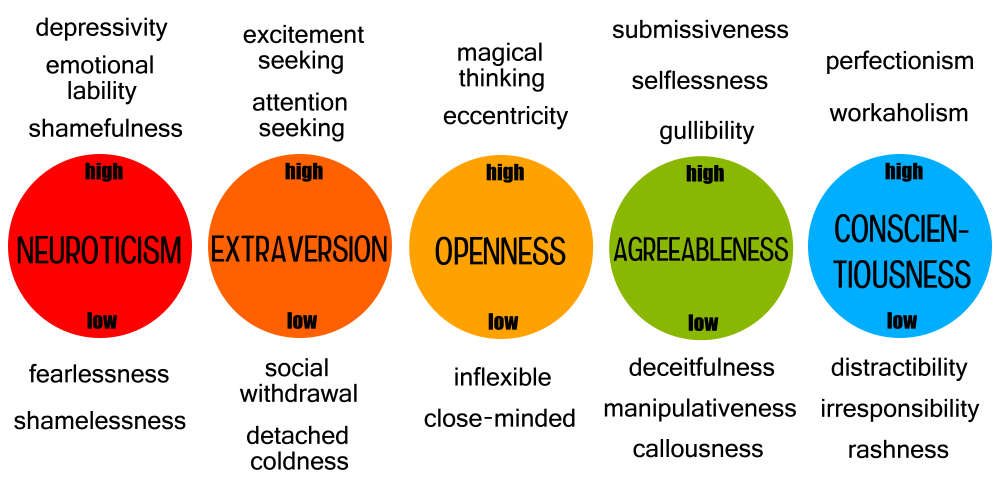

Other people are a favorite focus for her curiosity. To this end, she likes to apply a psychometric tool known as the Big Five that measures temperament in five domains. Conscientiousness places people somewhere between responsible and careless. Extraversion ranges from outgoing to solitary. Neuroticism, or a tendency to experience negative emotions, ranges from nervous to confident. Agreeableness goes from friendly to frankly critical. Openness to experience, representing a willingness to explore, ranges from the cautious to the curious.

Andrea has scored above the ninety-fifth percentile in extraversion, with very high openness to experience as well, which isn’t surprising for someone who enjoys intellectual exploration. She also scores highly on agreeableness, coming in around the ninetieth percentile.

The thing about Twitter is that you can easily use it to satisfy your openness, cruising around and asking all manner of people questions, but it’s a lot harder to express your agreeableness—especially at the same time. Agreeable people want to make others feel good. In person, body language does a lot of the heavy lifting here; we also usually have a shared history to draw on when we’re trying to understand another’s perspective. Instead, it’s just a question. And people seem pretty likely to “hear” a question in a negative tone when they’re reading it on a screen.

Andrea’s openness has led her to find friends who don’t share her core beliefs. This means that whatever she wants to explore, there’s a good chance that there’s someone in her circle who will get upset by it.

I asked Andrea how she navigates this. “I enjoy seeing people answer my questions, but I don’t like dealing with negativity and disagreement,” she told me. “[So] I’m really careful with my words online. It’s safer to talk about things I’m wondering than to make statements about things I believe and think.”

Andrea’s openness has led her to find friends in a wide range of communities, including some who don’t share her core beliefs. This means that, whatever she wants to explore, there’s a good chance someone in her circle will get upset by it. And online, you’re talking to everyone at once, possibly including strangers and even enemies. You can’t tailor your views to each individual in a way that allows you to acknowledge their particular views and feelings. This can quickly put a strain on a relationship. It might also make the agreeable questioner want to give up.

When Your Relationship Has an Agreeableness Gap

Then there’s the fact that not everyone agrees it’s so important to acknowledge another’s feelings. We can describe those people as lower in agreeableness. Here, too, the Big Five has helped Andrea make her way through the online intellectual community.

“I think understanding personality helps you to understand yourself and others, so that you can take yourself out of anything personal,” she told me.

For starters, it’s helped her recognize the type of person with whom she’s most comfortable: laid back, similarly open, and usually introverted. “I just like that type of person. I’ve surrounded myself with them!” she told me with a laugh, adding that she’s by far the most extraverted person in her circle of friends.

The Big Five lens also helps her neutrally assess those with whom she doesn’t click. It allows her to “take away a little of the personal hurt, if I don’t get along with someone.”

Consider people with high intellectual openness but low agreeableness. We might surmise that people like this are less likely to feel their questioning reined in by social pressures, which might then lead such people will dominate spaces dedicated to intellectual exploration. When they dispense with the pleasantries we use to reassure each other that we’re friendly, those who rely on such signals might perceive rejection. And that doesn’t feel very good.

“Being liked is very important to me, unfortunately,” Andrea said. In principle, she believes that you shouldn’t worry about what people think about you if you’re standing up for something you believe in (“It gets in the way,” she said). But this is easier said than done, and she doesn’t always manage to live by this principle. “But I’ve begun to learn that sometimes, it’s not about people not liking you,” she added.

If I understand that it wasn’t them not liking me—it was just them being blunt—that helps me to move on.

Gender norms can compound the issue. “With men, they’re a little bit more blunt, and often—not always, of course!—lower on the agreeableness scale,” she observed. “Why fuss with wording to say the thing? But for me, I need the cushion.”

As she’s engaged in highly open spaces, Andrea’s been trying to go without that cushion. “I’m starting to understand that maybe I need to reframe it and not take it personally when someone is blunt. If I understand that it wasn’t them not liking me, that helps me to move on. It’s learning to read them well.”

When They Actually Dislike You

Clearly, if we could let go of our fear that we’re disliked when we’re really not, that would lighten our burdens considerably. But what about when people truly don’t like us?

Andrea knows that this happens, too. “They’re people who are more serious—‘Andrea, get your head out of the clouds and stop being a silly girl! Oh my goodness, does this girl understand reality!’” was how she perceived her detractors’ assessment of her. As she acknowledged, this is an assumption; she can’t read their minds. But in at least some cases, her assumption is probably accurate.

And this led her, for a time, to hold a common defensive belief: If people just got to know me well enough, then they would like me. It was only when her pastor brought it up in a sermon that she realized she believed that—and that it was a fallacy. “I believed that—‘Oh, they just don’t understand me, they think I’m just this flighty girl, but I really have a lot of substance! If they saw me as I really am, I’m confident they would come to like me!’ But the thing is, that’s not always true. There has to be a percentage in the world who, if they really did get to know me, still would not like me. And that goes for everyone.”

Indeed it does. It’s a realization that can be freeing, especially for those who add the cherry of perfectionism on top of their highly agreeable sundae. If it’s impossible to get everyone to like you, then it’s not a failing when someone does not.

I know for a fact that there are some that I rub the wrong way. It’s coming to terms with that, and then adding, “And that’s okay. Not everyone has to like me.” Those words sound so good and enlightened. I wish I believed them for real.

“You said in our pre-meeting back-and-forth that everyone likes me,” Andrea remarked. “But I know for a fact that there are some that I rub the wrong way. It’s coming to terms with that—and then adding, ‘And that’s okay. Not everyone has to like me.’ Those words sound so good and enlightened. I wish I believed them for real.”

Facing Unkindness

It’s one thing to recognize the truth of these words on reflection, outside of the direct experience. It’s another thing to recognize it when you’re directly engaged with your detractor.

Andrea doesn’t get in disagreements very often, but when she encounters someone who seems not to like her, she struggles. She strives to respond with rationality and authenticity (and from my perspective, she does a good job with this), but sometimes conflict still erupts.

Someone may even say something unkind.

(Some of you will read that last line as comic hyperbole. But those of us cursed with high sensitivity along with our agreeableness are clutching our tightened chests, nodding along, remembering that time when someone was unkind to us.)

Some of you will read that last line as comic hyperbole. But those of us cursed with high sensitivity alongside our agreeableness are clutching our tightened chests, nodding along, remembering that time when someone was unkind to us.

“And I understand not everyone would think it was unkind,” Andrea added. “Maybe I’m just on the sensitive side. ‘Oh, you’re one of those people who doesn’t like me, and I need to be okay with that! Moving on!’ That’s just not how it happens in real time—especially if I like them! If I like them and they don’t like me, that’s very difficult.”

While Andrea can reason away why men would not click with her, the fact that she understands the standard rules for women’s social interactions makes other women’s rejections that much harder to accept. Worst of all is when that woman seems like she should be compatible as a friend, liking the same things that Andrea finds deep and engaging. In that case, the lack of shared laughter and other friendly interaction begins to become achingly conspicuous.

Which Friendships Are More than Electronic Links?

It’s awful when this happens in person, in a shared space like a church or a workout group, but that, at least, is a challenge we’ve been dealing with since time immemorial.

Online, the dynamics change in ways we didn’t evolve to handle—and that can make things extra wacky. Internet culture is created by people who are trying to find others, as Andrea put it, “who they can relate to, who are on their same team.” But it’s superficial: “There’s a level of depth that you don’t reach because you don’t really become friends, because you are being almost mutually used for acceptance.”

Such relationships—and I have learned the same thing—are brittle. “I have lost some people I thought were friends, who I’ve interviewed on my show, who were not happy with how I was not doing this or that enough—because I’m a centrist through and through. I don’t cancel people, and I don’t stop being friends with people, and I don’t take a hard line on anything, except taking personal responsibility,” Andrea said. “I’m not going to say, ‘This person is so wrong, I’m not going to be friends with him.’ I’ve told people I disagree and asked them why they think that, but I don’t block them. But I’ve had people block me. And I thought we were friends.”

I’m not going to say, ‘This person is so wrong, I’m not going to be friends with him.’ I’ve told people I disagree and asked them why they think that, but I don’t block them. But I’ve had people block me. And I thought we were friends.

It raises an emotional question: If someone you’ve known since childhood cuts you off because of a stance you share, how strong was that “friendship,” really? In an age colored by political tension and mediated by the likes of Facebook, many are asking this question. After all, Facebook artificially lengthens connections that would naturally have faded; it also strips away body language and the personalization that goes into one-on-one exchanges offline, as we noted earlier. But strong friendships tend to withstand this pressure. If they don’t, perhaps, as Andrea suggested, “There was depth that was never achieved.” What’s lost may not have been a relationship, but the illusion of one—though that doesn’t keep it from hurting.

Whose Approval Really Matters?

It’s one thing to refuse to cut people off because they disagree. But what if we turn that around? How much do we draw people closer if they praise us and tell us we’re right?

Of course we want to be around people who make us feel good. But there’s a risk in that, too, as Andrea noted. Here she brought up another lesson from her pastor, Paul VanderKlay: “More than the ones who then turn on you, more than the detractors, beware of the clapping gods.” VanderKlay reminded his congregation that those who welcomed Jesus with palm branches one week crucified him the next. “I never forgot that,” she told me.

Though I’m not a person of faith, I appreciated the story Andrea shared next. Originally from Max Lucado’s Wemmicks: You Are Special, the story features wooden people who reward those who do good (or at least, things they like) by sticking stars on them and shame people who do bad or displeasing things by sticking dots on them. “Clever ones get stars; foolish ones get dots,” Andrea explained. “Sometimes people would put stars on people just because they had stars, and dots on people who had dots! It’s very similar to Twitter.”

One girl in the village, however, had neither stars nor dots. “People would see that she had no dots and they’d try to put stars on her, but they’d just fall off; people would see that she had no stars and they’d try to put dots, and they’d just fall off,” Andrea said. “And so the most dotted boy, he saw her and said he wanted to be like her—‘How do I get rid of my dots?’ And she was like, ‘Oh, I see the carver, the one who made us. I go and see him every day. I realized it doesn’t matter what the rest of the carved people think. He made me. What matters is what does the one who carved me think?’ So the boy goes and sees the woodcarver.

“Okay, yes, it’s very Christ-centered narrative,” Andrea conceded. “I’m so used to staunch atheists being like, ‘Yuck, get it away.’ But this can be a story for anybody. It’s not far off from finding the archetype—the ideal.”

As I said to Andrea, you don’t have to be religious to ask whose approval matters. Christians may see “the carver” and recognize it as Jesus Christ or God. But non-religious people could seek an ideal in other sources. In the theory of positive disintegration, Kazimierz Dabrowski puts forward the concept of the personality ideal. Admittedly, unlike religious teachings, sorting out one’s own personality ideal can feel a bit like putting together an extremely intricate IKEA bedroom set with partial, unreliable instructions. It requires that you have the confidence to trust that your vision is a good one and some way to check that you yourself are not deluded. Not being religious, I’d speculate, might be why I like exemplars and heroes so much. Dabrowski did say that the search for ideal examples and models is a part of spontaneous multilevel disintegration (e.g., Dabrowski 1996, p. 19), and it seems to me that studying exemplars—whether you see that person as the Messiah or just an ordinary mortal hero—is a good way to sketch what one’s own ideal ought to look like.

You can’t tie your identity to people liking you. There will be counterfeit things coming at you—things that are not good for you—and you want people to like you so you conform and change toward that.

I described Dabrowski’s concept of the personality ideal to Andrea and asked her if that resonated. “Yes!” she replied. Then she brought up an illustrative example: “People who are experts at counterfeit money don’t study counterfeits to become an expert. They study the original. They know the original backwards and forwards. They know what real money looks like, and that is how they spot an impostor. That’s the idea of going back to ‘What am I and what are my foundations?’

“It doesn’t matter what religion or lack thereof you believe in; all people wonder ‘Who am I? Where do I hold my identity?’” Andrea continued. “This is why you can’t tie your identity to people liking you. There will be counterfeit things coming at you—things that are not good for you—and you want people to like you so you conform and change toward that. That’s why you must study the original!”

Being Who You Are

This isn’t just an abstraction for Andrea. Those lessons about stars and dots and clapping gods—and about living up to an ideal—helped Andrea in her own effort to construct a healthy identity. “I am a believer in Jesus and I am a Christian, but I went through a time when I didn’t even like calling myself a Christian because I thought that I didn’t want to be associated with the assumptions that saying I’m a Christian comes with,” she told me. “People assume you’re judgey, that you don’t like hearing modern scientific takes.”

This presented a problem for Andrea because of her love of intellectual exploration. When that led her into a group of public intellectuals known as the Intellectual Dark Web [IDW], those stereotypes about Christians got in the way of the connections she was looking to form. “So I was going from the perspective that I’m not like one of those regular Christians, I’m a cool Christian,” she told me. “Whereas the rest of the fellows I was following on Twitter, they’re the ‘Science People,’ a little bit more [temperamentally] open” than the average Christian might be.

Suddenly, Andrea found she had a lot of atheist friends. What’s a highly agreeable Christian to make of such a fundamental difference? On the one hand, she loved intellectual exploration. On the other hand, she wanted to be honest—and feared rejection.

“I didn’t even want to talk about religion initially!” Andrea said. “I was just concerned about freedom of speech and thought. But I didn’t hide it! If something came up that I wanted to talk about and my faith was relevant, I didn’t hide it.”

Looking back, bridging that divide was a catalytic experience for her. “I feel like I’ve done the deconstruction—the disintegration,” she told me. “I actually call it my dark night of the soul. I would see such hypocrisy in the church—[talking about] loving one another and taking the plank out of your own eye, looking at the people and the dots and the stars instead of the original.” But her Christian friends didn’t always seem to care about the ideals in which they purportedly believed.

Spending time on Twitter listening to atheist detractors didn’t help her feel better. “I did find that being around the people who only believe in what they can see and touch, that really made me, I don’t want to say question my faith because I never became an atheist—I didn’t stop believing in God—but it made me question how I can believe this. And that’s another reason I didn’t want to be called a Christian: because I didn’t want to be associated with those people who were unquestioning.”

Happily, Andrea’s dark night has been brightening. A study of symbolism, starting with the work of Jonathan Pageau, helped her understand what she got from her faith that an ultra-intellectual view could not offer. “I was seeing where I was being led in this space that was very material and falsifiable, where if it’s not falsifiable it’s not true. Watching these videos on symbolism, I realized there are things that are more than true, that can’t possibly be falsifiable—virtue, love, wisdom!”

She emphasized to me that this isn’t a knock on the scientific method, which she holds in high esteem. “Scientists do amazing, important work so we can understand ourselves in this natural world,” she said. Some questioners will find it such a valuable tool that they will use it to chart the course of their lives. Other questioners will follow a path like Andrea’s, where the idea of metaphor and symbolism for the “truer than true” resonates deeply with them.

For the agreeable questioner, finding a way to remain open and curious about why others operate they way they do, and to truly agree to disagree when necessary, is an important life skill.

In the end, it comes back to those differences between people. For the agreeable questioner, finding a way to remain open and curious about why others operate they way they do, and to truly agree to disagree when necessary, is an important life skill. For me, Andrea’s story shows how understanding others and their paths, rather than pressuring us to follow, can help us chart our own way, and truly understanding others’ ideals can help us sort out and live up to our own.

Not everyone will see it that way. As we discussed earlier, that’s okay. There are enough open people out there that you don’t have to be lonely on this path, even if the social pressures make some of them go into hiding.

“For me, I want the truth, spoken in love with a little cushioning,” Andrea said. “If I’m asking people’s opinions, I really want to know. I don’t want to be humored. I like a genuine interaction with someone. That’s what I’m about.” Because, as you Third Factor readers will likely understand, “I am someone who is very ‘themselves’ wherever I go. I am not anyone else.”